Memory is a tricky preoccupation. It can take the form of saccharine nostalgia, a little soft at the edges and tinted yellow with age. It can emerge as clear and bright as the midday sun, or it can be ephemeral like snippets of a conversation or remembering something read in a newspaper or heard on a radio station. Like most people, my memories are a combination of all of the above. On occasion, I have to cross-reference with someone else or even several people to confirm or refute my remembered moments… ‘Did that really happen?’… ‘How did that story go?’

Stigma Damages is an archive and a body of artwork that I established from 2011 onwards, much of it stemming from my childhood experiences of having grown up on the periphery of an aluminium refinery. The artwork’s title is a legal term used to describe possible loss or suspected contamination due to heavy industry or activity that damages the environment, and is inclusive of the collective stories and reminiscences in the locale of life before the refinery, the massive overhaul to the regions infrastructure coinciding with the construction of this industry, and then the subsequent impact on the environment and animal and human health.

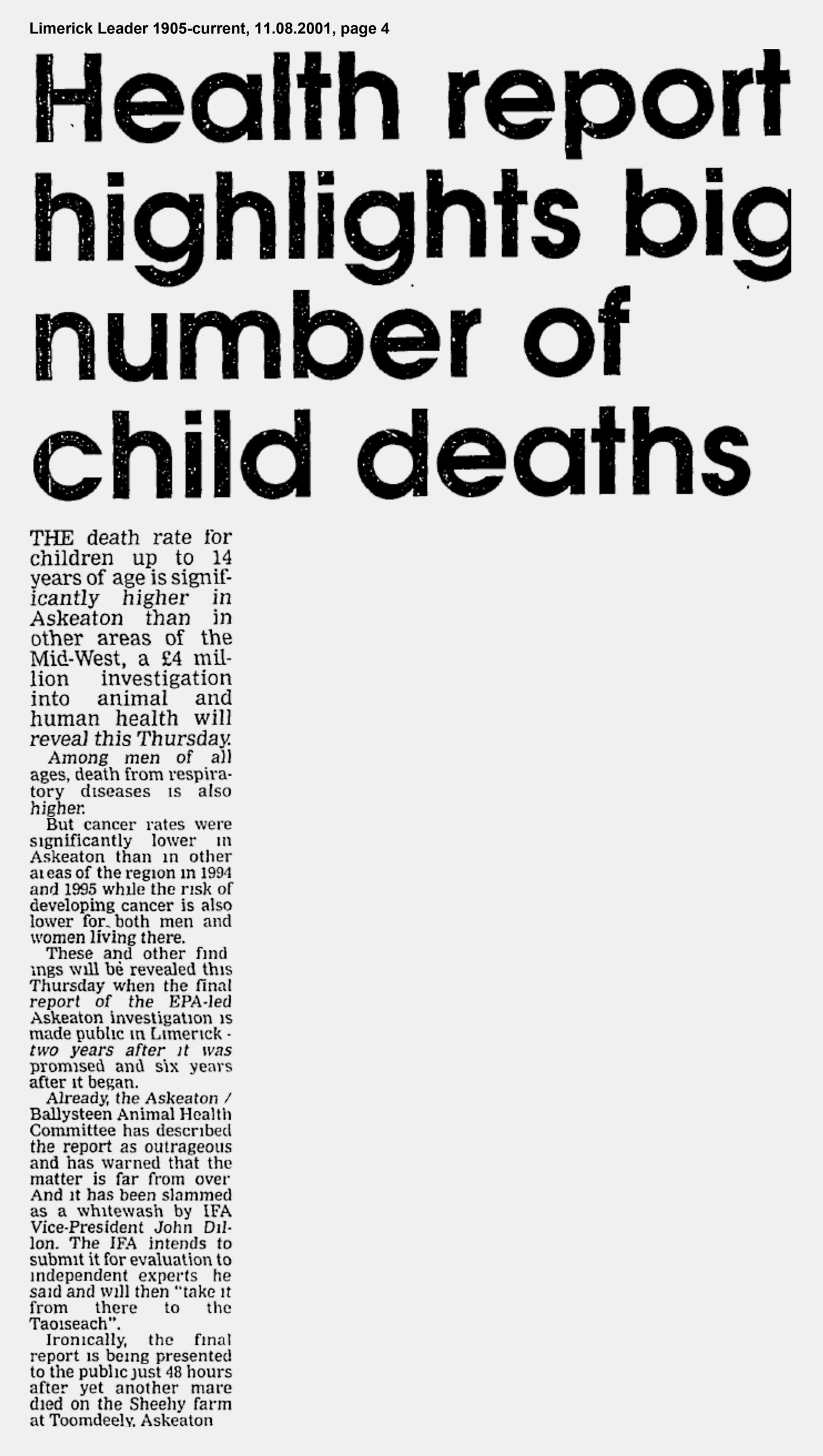

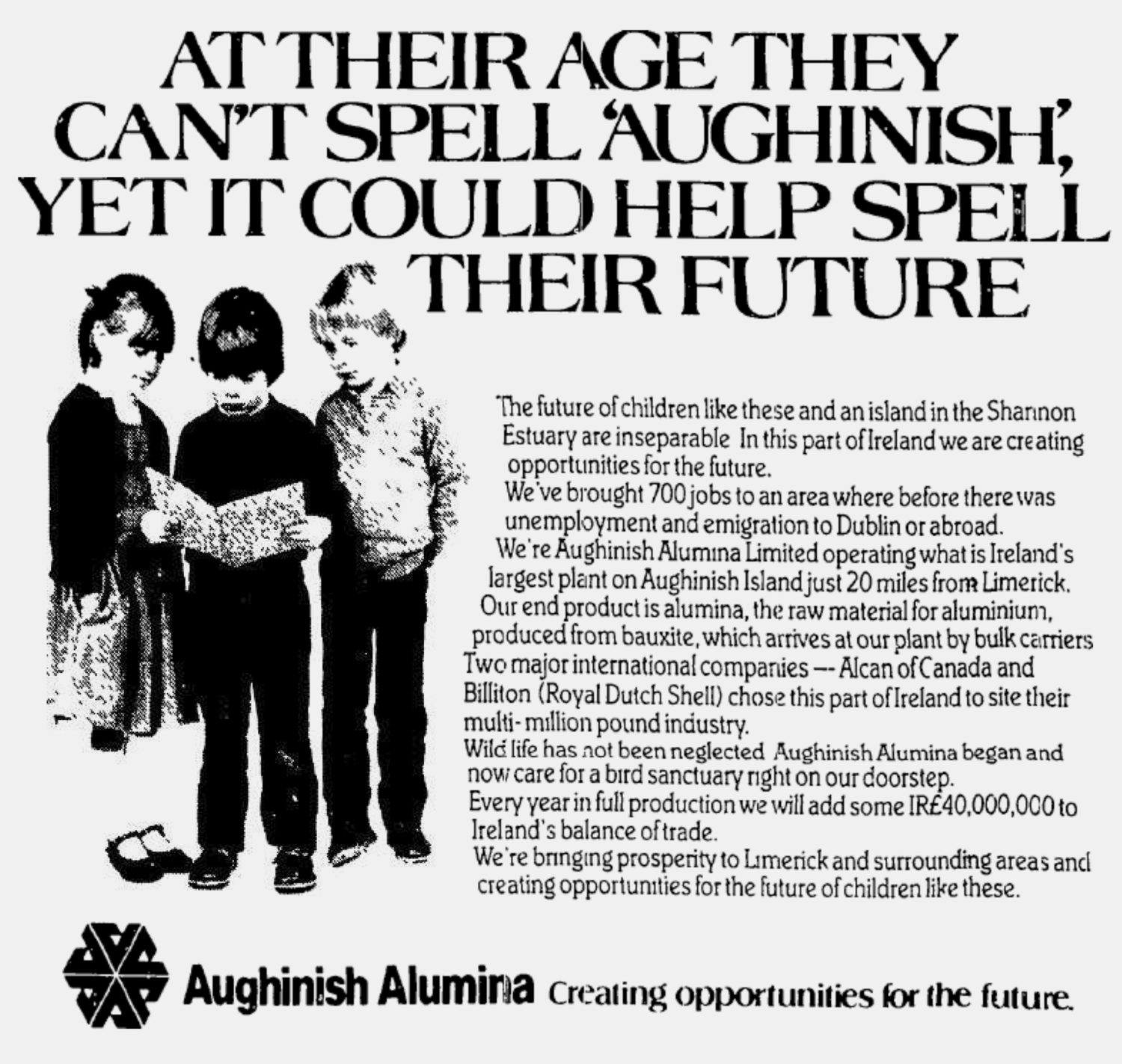

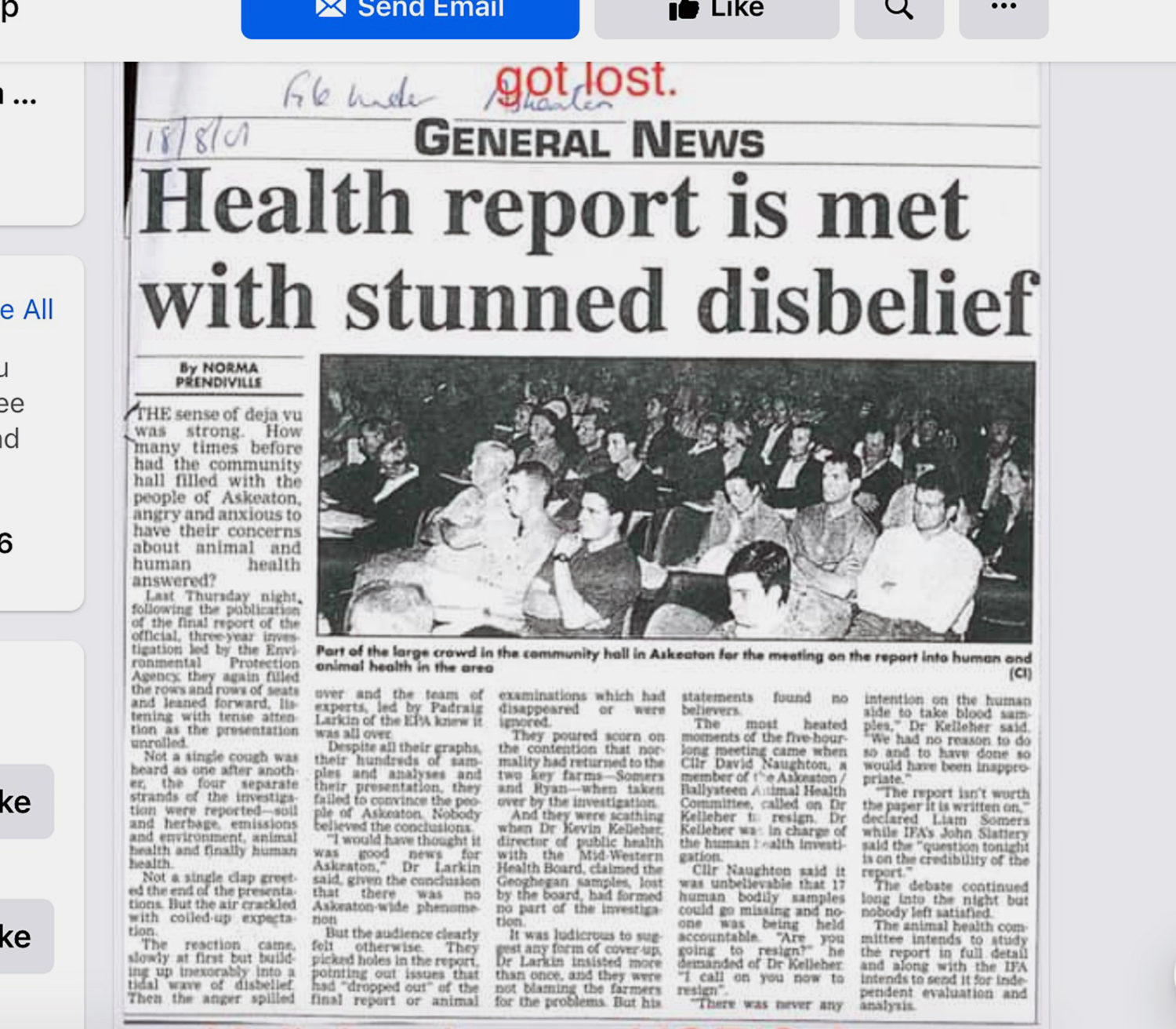

The site in question, Aughinish Alumina, is Ireland’s largest industrial complex, and Europe’s biggest bauxite refinery. Sitting on the Shannon Estuary that flows into the Atlantic Ocean, it began production in 1983. Currently owned by Rusal, a Russian consortium, red rock bauxite mined and imported from Guinea is chemically altered onsite to become white powder alumina, before being exported to smelters worldwide and transformed into aluminium. In the mid 1990s, the refinery hit the headlines, with hundreds of animals dying on farms located in the shadow of the plant. A four-year investigation by Ireland’s Environmental Protection Agency found no relationship between deformed agricultural livestock, local health, toxic deposits and harmful caustic emissions emitted through large smokestacks – instead it blamed management practices of local farmers leading to poor nutrition, resulting infection and the death of animals. Independently-funded academic reports found otherwise, and inevitably attributed causality to the refinery’s activities.

Nowadays, as a major economic driver and employer in the region, the plant has more or less carte blanche from the Irish state to do whatever it wants. An expansive storage area for red bauxite residue mud, a by-product of the manufacturing process continues to exponentially grow onsite to over 350 acres, with aggressive rock blasting to extend its size being completed in close proximity to the river estuary. The mud, full of chemicals, was classified as hazardous for years until the EPA began to describe and define it as ‘non-hazardous’ since 2003. On a recent visit there with an environmentalist friend trained in reading and analysing the technical information in the annual report that is only available at the reception area of the refinery, we learned that Rusal are not required by Ireland’s EPA to survey the health of any marine wildlife in the vicinity of the complex, and that legal requirements of making public real time monitoring of emissions are currently not complied with.

Such scenarios have driven activist groups such as Rescue the River Shannon and Limerick Against Pollution to lobby and raise awareness of these continuous problems, highlighting industrial disregard for environment through agitation on local political platforms, social media, a documentary (linked here on the EVA International website), and a current search to seek out whistleblowers to come forward to help in their independent, ongoing investigations. These are by no means the acts of a hopeless people, rather this is slow, steady and deeply invested – a marathon and not a race – with every action hard won.

Remnants of these experiences live forever in a community, raw and disturbing stains that, no matter how many ‘good news’ stories come through (usually generated through economic achievement or corporate spin), cannot conceal the ugly that remains on the surface and in the air. This is what eco-anxiety is, like Shakespeare’s well known character Lady MacBeth, uttering the line ‘Out damned spot’, in a play I studied for my Leaving Certificate examination in a school and in a community shadowed by an industrial demon. In Robert Allen’s 2004 essay ‘Askeaton: In the Shadow of the Dragon’, he lays out concerns about the impact such an industry has on the ecology of the area, seeping into all aspects from flora to fauna to human life, and evocatively quotes playwright Walter Macken,

In large communities it is called rumour but in small communities it is knowing. You cannot hide real events and call them by another name, because men are not fools and if you give them the evidence of their ears and eyes, and even with a minimum of intelligence, they can piece together all the facts.

I’ve worked closely in my studio with Niamh Moriarty, a fellow artist and adept researcher in finding newspaper articles on Aughinish. Intermittantly over several months, Niamh would search, download and file a substantial amount of material yet, strangely, when we reviewed them there seemed to be very few reports appearing about animal deaths in the region, something I could remember as being covered in national and regional media. Niamh takes up the story in this explanatory note:

We used keywords, ‘Aughinish’, ‘ALCAN’, and ‘Rusal’ for initial searches, completed between November 2019 and June 2020 using the Irish Newspaper Archive and Irish Times archive online. The initial three searches came back with information directly relating to the business and planning at the Aughinish Alumina Refinery, as well as mentions of sports and community sponsorship, third level research initiatives and on-site planning permissions. More content appeared on industrial labour action (1980, 2019), shipping accidents (1990, 2012), and economic growth, more recently with the threat of US tariffs.

After Michele stumbled across a news article posted on Facebook by Rescue the River Shannon relating to the EPA’s publication of an animal health report in Askeaton in August 2001, we conducted more searches, not using the name of the factory but rather terms such as ‘environmental protection agency askeaton’, and ‘health askeaton’. These came back with articles on animal health in the refinery’s environs, particularly the EPA’s 1996–1998 probe into sudden animal deaths around the town of Askeaton. There appears to be a dissociation between the reporting on the refinery’s activities and its effect on the local neighbourhoods, as many of these articles do not cite the refinery by name as a potential threat to human and animal health along the River Shannon or in the West Limerick region.

In an age where finding information has never been so easy, clearly there are still ways to manipulate the search engine, to rewrite a history to suit your own story. It can be no coincidence that the name of the company has been protected here, and perhaps something to do with potential libel action.

If we are going to deal with these monsters, it is our responsibility to know of their actual lineages, as with this knowledge we can have a more accurate autonomy over our memories. This ultimately make us act in a particular way here and now, to stay vigilant and ask the hard questions.

Originally printed in October 2020 as part of EVA International’s research blog Little Do They Know, curated by Merve Elveren. Much of this text was influenced by Notes from the Belly of the Beast, a text I co-authored commissioned by Dundee Contemporary Arts in 2020. For this, I thank Stuart Whipps and Eoin Dara.